Introduction

Cardiac masses may be divided into two categories: neoplastic or, most commonly, non-neoplastic (Table 1)1. Frequently, non-neoplastic clots or vegetations are found in clinical conditions such as arrhythmias, such asatrial fibrillation and left ventricular apical infarcts, on the one hand, or infective endocarditis, on the other2, 3.

In turn, neoplastic lesions may be classified as primary or secondary3. Between 80% and 90% of primary neoplasms are benign, mostly myxomas, in adults2–4. The prevalence of secondary cardiac tumors (metastases to the heart) is higher than primary tumors, with a ratio of at least 20:15,6.

Cardiac metastization can occur by direct invasion of the primary tumor, hematogenous (arterial or venous), or lymphatic spread (often seeding the pericardium or the endocardium)2,3.

The neoplasms more commonly associated with cardiac metastization are thoracic carcinomas (lung, breast, esophagus) followed by hematologic malignancies and melanoma (which displays the highest propensity)1,3,7.

The location of cardiac masses usually conveys information on their etiology. Myxomas and most sarcomas tend to develop in the left cardiac chambers, while angiosarcomas are usually diagnosed in the right atrium2. Cardiac metastases are more common in right cardiac chambers because the lower blood flow favors the anchorage of cancer cells. On the other hand, valve involvement is rare in such settings due to constant movement and poor vascularization7.

The diagnosis may be incidental or the result of cardiac symptoms investigation1.

Case report

A 67-year-old man without any relevant medical or family history, a former smoker, presented with macroscopic hematuria and was diagnosed with bladder cancer (high-grade urothelial carcinoma). He didn’t undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy due to a perioperative embolic stroke and has, instead, subjected to radical cystoprostatectomy, with the construction of an ileal conduit (Fig. 1). The pathological stage was pT3bN2M0.

A year later, during surveillance, lung, bone, and lymph node metastization were detected. He started chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine, but the treatment was stopped after fivecycles due to ototoxicity. As he accomplished partial response, he continued maintenance treatment with immunotherapy (avelumab, an anti-PD-L1 antibody).

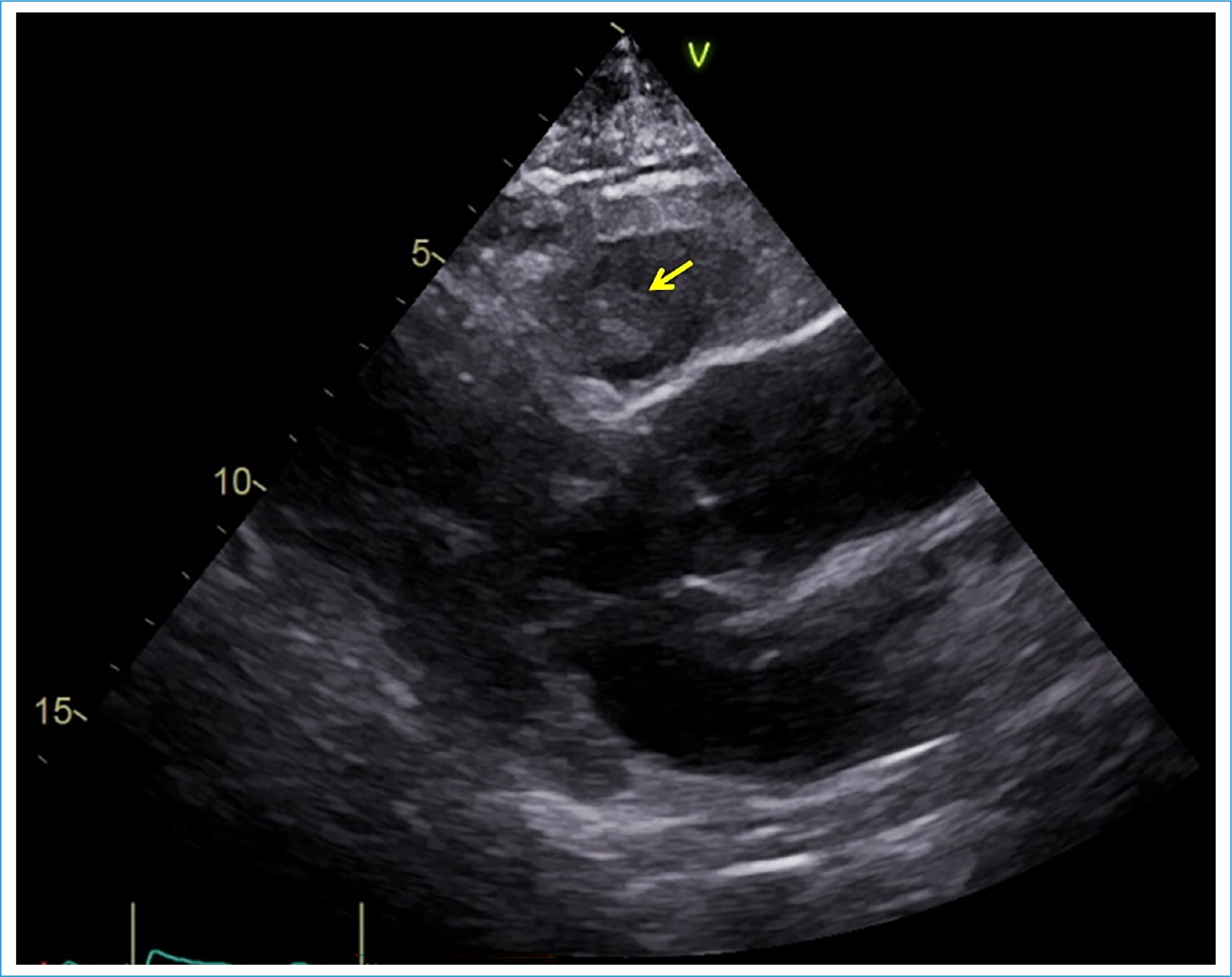

In August 2021, after 3 months of immunotherapy, the patient underwent thoraco-abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) for response evaluation. This exam revealed a mass in the right ventricle (axial dimension 52 × 29 mm, longitudinal dimension 80 mm), reaching the emergence of the pulmonary artery. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) confirmed a mobile non-obstructive mass anchored in the free wall of the right ventricle (Fig. 2), without any other significant cardiac alteration, measuring 25 × 30 mm. The patient was asymptomatic and his physical examination was unremarkable. Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging was not available in our institution. A 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-CT (18FDG PET-CT) was instead performed. The exam showed high 18FDG uptake in the right ventricle mass (Fig. 3), supporting the hypothesis of a metastatic nature.

It is important to note that, despite the patient’s good performance and asymptomatic status, metastatic bladder cancer usually carries a poor vital prognosis. On this account, and due to disease progression during immunotherapy, a new treatment line with a taxane was proposed. However, the patient developed grade 4 thrombocytopenia. The bone marrow aspiration revealed a high number of megakaryocytes. The case was discussed with Hematology, and the most likely diagnosis was avelumab-induced thrombocytopenia. Although the patient received γ globulins and corticosteroids, thrombocytopenia was treatment-refractory and contraindicated chemotherapy. Meanwhile, he presented clinical deterioration due to disease progression and died in October 2021, 2 months after the cardiac metastasis diagnosis.

Discussion

Bladder cancer is the 10th most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide8. In Portugal, bladder cancer has the seventh highest incidence and eighth highest mortality rate among all cancers (4.3% and 4.0%, respectively)9. Most frequently, metastization occurs to regional nodes and later to the lung, liver, bone, brain, and subcutaneous tissue10. Cardiac metastasis of bladder cancer is a rare condition, only described in a few case reports11,12.

There is no established diagnostic approach for such a condition, but imaging is essential. Diverse cardiac imaging modalities are available, including TTE or transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), CMR, cardiac CT (CCT), and 18FDG-PET1,2.

Table 1. Cardiac masses: most common etiologies1,2,6,15

| Cardiac masses | Type | Most common location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-neoplastic | Crista terminalis | Atria (right) | ||

| Intracardiac thrombus | Ventricles | |||

| Lipomatous hypertrophy | Atrial septum | |||

| Non-neoplasmatic calcified masses | Posterior mitral annulus | |||

| Pericardial cyst | Pericardium | |||

| Valvular vegetation | Valves | |||

| Neoplastic | Primary tumors | Benign | Fibroma | Ventricles |

| Hamartoma of mature cardiac myocytes | Ventricles | |||

| Hemangioma | Ventricles | |||

| Lipoma | Pericardium | |||

| Myxoma | Atria | |||

| Papillary fibroelastoma | Valves | |||

| Paraganglioma | Atria | |||

| Rhabdomyoma | Ventricles | |||

| Malignant | Angiosarcoma | Atria | ||

| Lymphoma | Pericardium | |||

| Mesothelioma | Pericardium | |||

| Myxofibrosarcoma | Atria | |||

| Osteosarcoma | Atria | |||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Ventricles | |||

| Solitary fibrous tumor | Pericardium | |||

| Secondary tumors | Metastatic | Atria, pericardium | ||

TTE is usually the first diagnostic approach because of its widespread availability and its high sensitivity and specificity in the detection of cardiac tumors (90% and 95%, respectively)13. However, TTE may be insufficient to determine the extent and origin of the mass and could be limited by patients’ characteristics such as obesity or chronic lung disease1,3,4. If a valvular lesion is suspected, a TEE should follow3. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or CCT are useful examinationfor mass characterization since some of itsfeatures may suggest a malignant nature (for instance, multiple and large lesions, irregular margins, modest to intense enhancement, or signs of infiltration)1,14. If a malignant etiology is suspected, 18FDG-PET may provide a more accurate determination of myocardial and pericardial involvement3.

Histological confirmation would theoretically be necessary for both diagnosis and appropriate management of intracardiac masses, mostly if a primary cardiac cancer is suspected13.

Clinical presentation depends on tumor location and size2,3. Most cardiac masses are asymptomatic or associated with mild symptoms2,7. However, cardiac tumors may present with heart failure symptoms, angina, syncope, electrical disturbances (including fatal arrhythmias), and even constitutional manifestations2. Pulmonary and/or systemic thromboembolic phenomena may occur since tumor fragments or thrombi that form around the tumor may well get access to the circulation2,3,6,13. Pre-disposition to embolic events depends on tumor characteristics, with small tumors with friable surfaces more frequently implicated13. Paraneoplastic phenomena such as hypercoagulability are also possible, potentially leading to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis and recurrent thromboembolism15.

Figure 1. Timeline of the patient’s medical and surgical history. ChT: chemotherapy; IT: immunotherapy.

Figure 2. Transthoracic echocardiogram performed on admission, parasternal long-axis view. Yellow arrow: intracardiac lesion.

There is no standard treatment5. The documentation of cardiac metastases is associated with advanced-stage disease and consequently, the treatment goal is usually palliative and focused on the control of the underlying cancer3,7. However, despite the poor prognosis of cardiac metastization, surgical treatment may be considered5. Surgical excision is only an option in selected conditions, namely significant hemodynamic repercussion or solitary metastization in a patient with an expected relatively good prognosis3.

Figure 3. 18Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (18FDG) images demonstrating a large mass with high 18FDG uptake located in the right ventricle.

The estimated incidence of cardiac metastasis is 0.7-3.5% in the general population and 9.1% in patients with metastatic cancer, sometimes with post-mortem diagnosis5,15. The incidence of cardiac metastasis is increasing, probably due to greater overall survival of cancer patients and to the common use of non-invasive cardiac imaging in asymptomatic patients4,7.

Conclusion

Despite being a rare condition, the early diagnosis of intracardiac metastasis is crucial due to its implications on patient treatment and prognosis and should always be considered a differential diagnosis in the setting of an intracardiac mass. Cardiac imaging may lead to the diagnosis, especially in a patient with a cancer history.

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical considerations

Protection of humans and animals. The authors declare that no experiments involving humans or animals were conducted for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The authors have followed their institution’s confidentiality protocols, obtained informed consent from patients. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this manuscript.